My PhD thesis project

Towards a better understanding of human-exoskeleton interactions

Contexte & Introduction

Exoskeletons captivate the collective imagination thanks to their portrayal in the media, often depicted as conferring superhuman strength or offering the hope of mobility to people with motor disabilities. However, the reality of these devices is far more complex. Indeed, although they can offer significant improvements in physical capabilities or even replace lost functions, it is essential to recognize that their use can lead to disruptions in motor control, as a consequence of close and repeated interaction with the human body. The question of the long-term effects of using exoskeletons is of particular concern, especially in industrial environments where their use is envisaged over long periods in order to reduce the risk of musculoskeletal disorders (MSDs) linked to repetitive tasks or the carrying of heavy loads. Previous studies have focused mainly on the effect of force fields at the end-effector (the hand), neglecting the specific effects of exoskeletons, which interact at the joints via several attachment points.

Recently, research has focused on the impact of exoskeletons on the human body, examining adaptation to force fields applied to the arm

In this context, my research aims to explore the long-term impact of repeated use of exoskeletons. My aim is to study changes in the spatial and temporal coordination of human joints before and after the use of these assistive devices. Indeed, to date, no studies have looked at the changes that persist once the exoskeleton has been removed, or at the effect of wearing an exoskeleton repeatedly. However, these questions are crucial to the safe development of exoskeleton use.

Material & Method

Human Movement Analysis :

An essential element of this work is the measurement of human joint angles with and without an exoskeleton. I use the motion capture system Optitrack, which uses sensors attached to the body and infrared cameras to obtain precise tracking of movement. These data are processed by various algorithms I’ve developed to reconstruct and extract the arm’s kinematics.

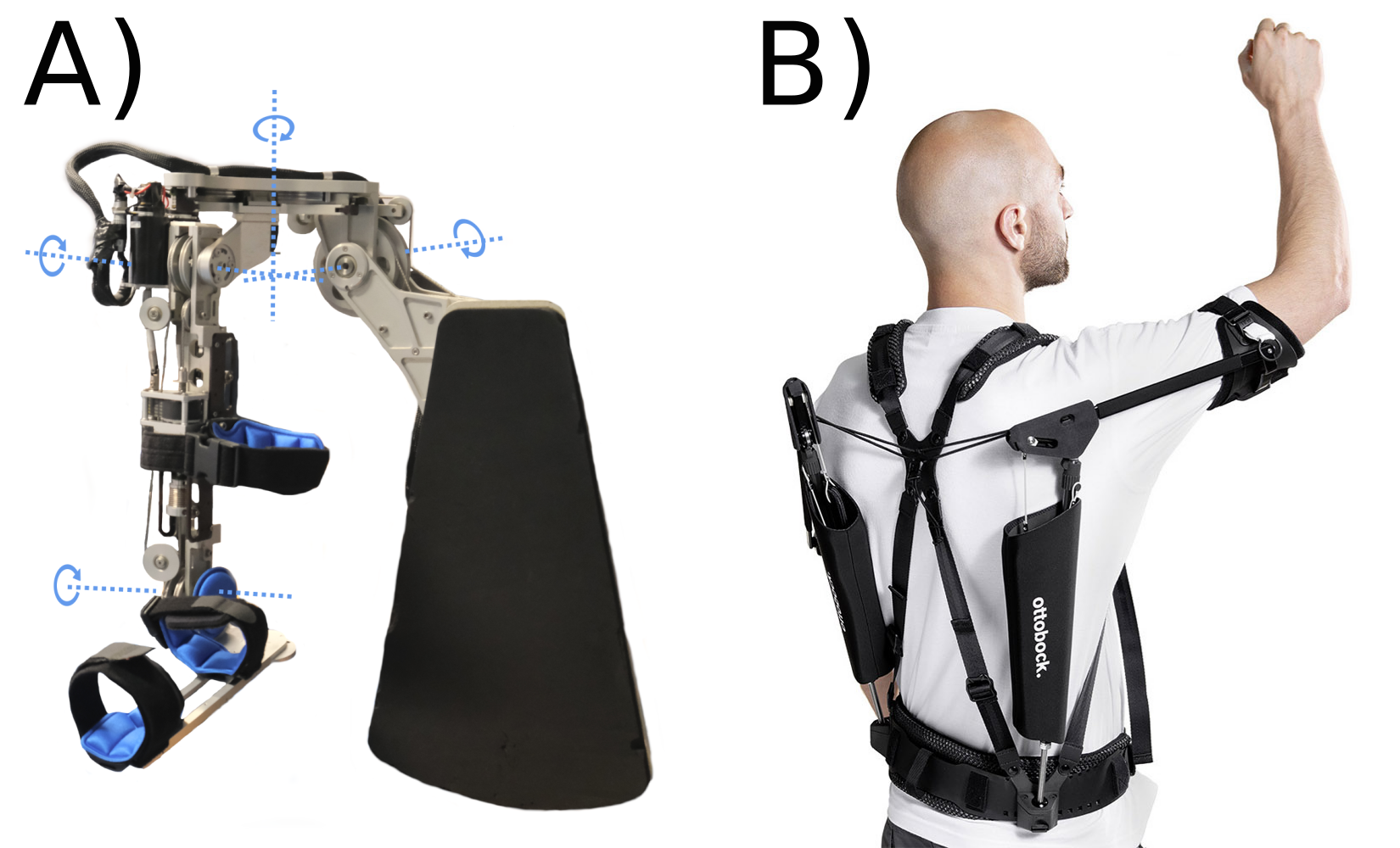

Exosqueletton :

The exoskeleton used is a right-arm robotic exoskeleton, ABLE, developed by CEA-List \cite{Garrec2008} (Picture A above). Future studies will also include the evaluation of a passive commercial exoskeleton already in use in industry, the PAEXO (Picture B above), to verify the transferability of results to commercial exoskeletons.

Force Fields

To model different situations and behaviors exhibited by commercial exoskeletons, I defined and coded on the ABLE robotic exoskeleton, five low-amplitude force fields, representing the interaction faults typical of these devices. The Transparent force field enables the exoskeleton to compensate only for its own weight. The Viscous field simulates poorly compensated viscous friction. The Elastic field reproduces the effects of poorly adjusted springs. The exoskeleton’s Gravity Decreasing field is designed to over-compensate for the weight of tools or the human arm, giving a sensation of lightness. Finally, the \textit{Gravity Increase} field reproduces situations in which the exoskeleton does not sufficiently compensate for the weight of the arm and tools.

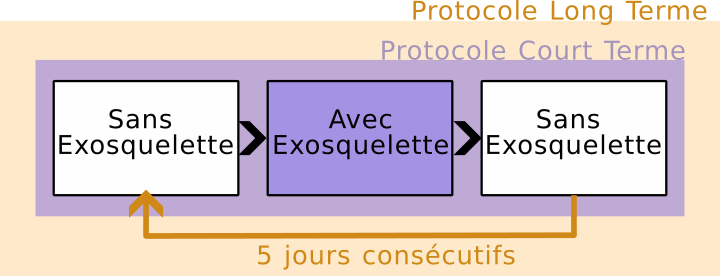

Protocol

The experimental protocol (presented above) consists of repeated pointing gestures, without, with (20 to 30 min), then again without the exoskeleton, the latter simulating one of the 5 perturbations. The aim was to compare inter-articular coordination strategies before and after exposure to the exoskeleton. This first protocol, which lasted one hour and involved 55 people, was designed to observe the short-term effects of wearing an exoskeleton.

In the second experiment, the first protocol was repeated five days in a row, with the aim of observing changes in the coordination strategies of the same participant, following prolonged exposure to a weakly disruptive exoskeleton. In this experiment, only the force fields most representative of real-life situations in industry were tested: the Viscous and Decreasing Gravity fields. A total of 16 subjects are being included in this protocol. In each protocol, a further 8 subjects performed the task without an exoskeleton, in order to assess the natural variability of human movements and provide a baseline.

Metrics

Measuring the evolution of joint coordination represents a major challenge, as it involves analyzing changes in spatial and temporal coordination between different joints. To date, no existing metric is able to assess these two aspects of coordination while giving a physiologically explicable result (list of publications [4]). To overcome this difficulty, I have developed two new metrics (list of publications [2]), based on different mathematical tools, to take into account the specific challenges of inter-joint coordination. In addition, I am also analyzing classic metrics from the literature, (task completion time, hand speed), in order to compare these results with those reported in other studies.

Results

Initial results show that even brief use of an exoskeleton affects joint coordination, without altering the performance of users’ hand movements (list of publications [3]). The different perturbations studied do not have the same impact on coordination characteristics: the elastic field seems to have a greater influence on temporal coordination, while the viscous field seems to mainly affect the contribution of each joint to task performance.

Initial observations from the 5-day experiment show a stability in the characteristics of users’ hand movements over the 5 days, but a progressive evolution of coordination strategies after each exposure (Fig. \ref{fig:coord}, list of publications [1]). In parallel, I am working on individualizing the analysis of participants’ data to provide personalized recommendations on the use of exoskeletons, aimed at limiting the deterioration of motor strategies and the onset of MSDs in the long term.

Discussion & Conclusion

These initial studies explore the impact of an exoskeleton on joint coordination, once the exoskeleton has been removed and during repeated use. As this aspect has not been addressed in the literature to date, these results open up new avenues for understanding human-exoskeleton interactions, and open up the possibility of developing these devices in a way that is safe for their users. However, a number of questions remain to be answered. The first is the transferability of these results to everyday life. The experiments were carried out on a specific task in the laboratory. Are these results directly transferable to other everyday activities once they have been taken out of the experimental framework? A second question concerns the transfer of these results to commercial exoskeletons. Indeed, although the disturbances generated are as close as possible to those encountered on industrial exoskeletons, they remain specific to this exoskeleton. Validation of these results with commercial exoskeletons is therefore necessary, and my next experiments will be directed in this direction. In conclusion, these initial results show that repeated use of an exoskeleton affects joint coordination, although it does not affect hand trajectories. The changes in coordination observed are proportional to the length of time the exoskeleton is used, and could lead to MSD over the long term. It is therefore necessary to focus on inter-articular coordination when setting up these devices, and not just on the hand. A better understanding and individualization of these results would enable us to identify ways of improving these devices and make recommendations concerning their use. These results could also open up new perspectives in rehabilitation, given that the effectiveness of rehabilitation with an exoskeleton remains limited to date.